Germany’s well-known bureaucratic mire comes to light when Valya tells me about how she asked to be officially reassigned to Berlin. Her first host family had not been a good match for her emotionally, nor had Bremen been workable financially, even with a government stipend. She wanted to make sure her new hosts would be compensated for offering to host her in a situation that was more copacetic. The official at the Department of Immigration-such-and-such sternly told her that she and her original hosts would only be given a stipend if she stayed in the Bremen area.

Put simply, she would be required to stay with the unkind family that had seemingly only agreed to take her in on the fly because the German government would pay them for it.

When it comes to bureaucratic red tape, Germany is infamous. And for a sensitive empath like Valya, the impersonality of it is soul-crushing. She doesn’t understand why she can’t simply move if her living situation is not a good fit, especially when the country in question is rich and developed enough to allow her to do so easily. There’s a resistance to allowing her to make her own decisions. It is a resistance that seems less to do with logic and more to do with a controlling adherence to a protocol that serves no one.

This is where one of the worst complications of the refugee experience can arise: the host country’s inability to safely, effectively, and considerately absorb and integrate an influx of refugees into its societal fabric. A refugee, unlike an immigrant, has not chosen to re-establish in another country. They have not carefully prepared for their departure and built a skill set with the intention to pursue a dream of economic stability or personal freedom in a new home. They often have little to no control over where they go. In fact, what designates a refugee according to Amnesty International is that they are “a person who has fled their own country because they are at risk of serious human rights violations and persecution there.”

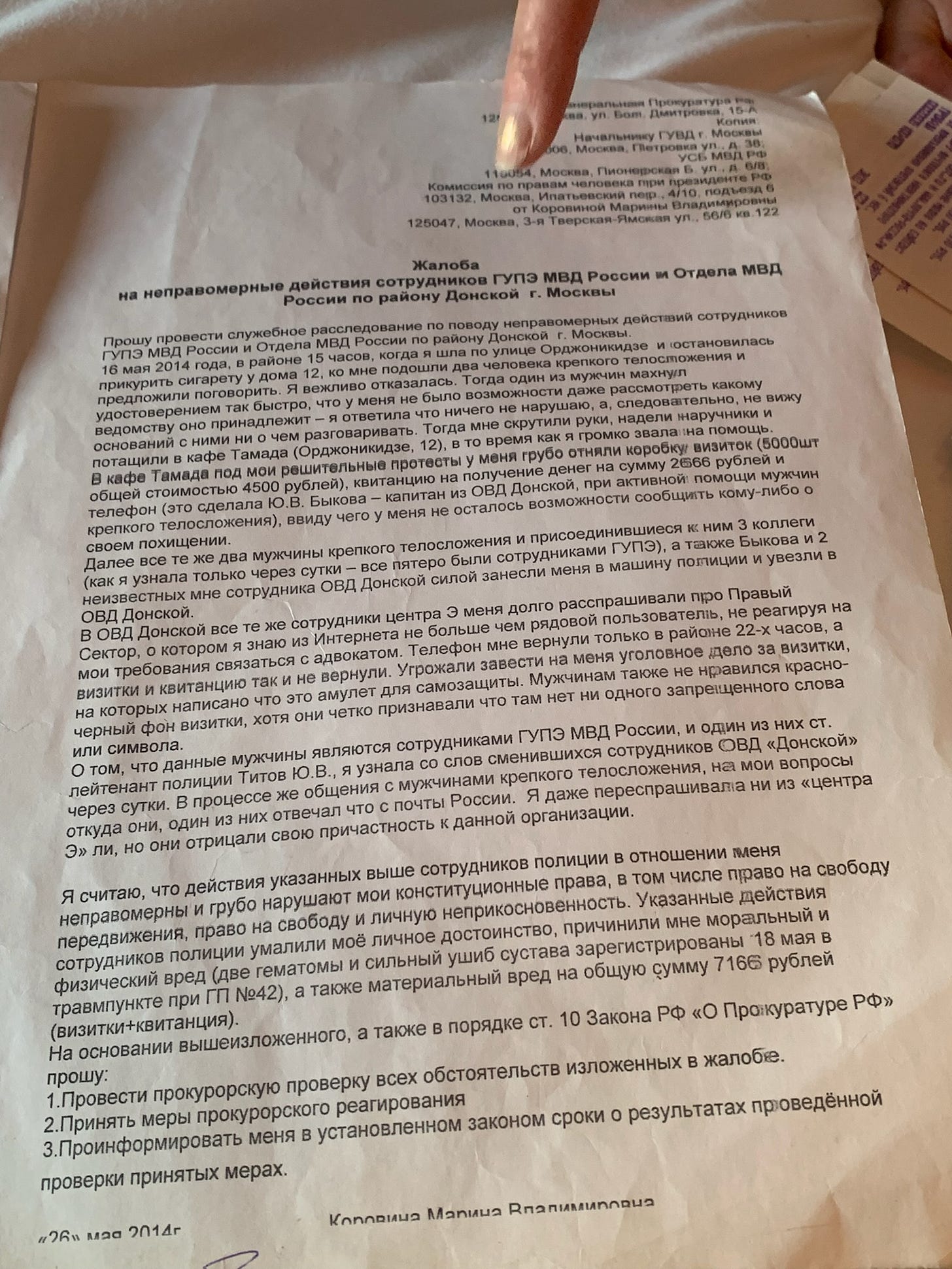

For some ninety million displaced people worldwide, the sense of choice-making so central to personal power and confidence has been stripped away. Often these displaced, disempowered people have also suffered assault, robbery, and bribery (to name a few) as they flee imminent mortal danger.

Valya doesn’t want to make her home elsewhere. She never decided to leave Ukraine. She never agreed to submit to a dehumanizing bureaucracy in a foreign land. She doesn’t want to be in a place where a family or a government can reserve the right to turn her out if she voices a preference or indeed uses her voice for any reason at all. This fundamental, almost spiritual chafing is one front and center for every refugee I’ve worked with since 2007. When I am lucky enough to take the time to deeply “hang out,” their journey of immense spiritual pain comes to the surface. It’s an ongoing burn on the skin of the soul, a burn that often doesn’t get the chance to heal.

Valya wants nothing more than to get back to Odessa, where she has a cheerful little tan-colored condo and a studio space all her own. Valya had done the work so many single mothers do once they have raised their children: she reclaimed her fantasies as more than just silly inclinations. She had begun to grow a business in Odessa. It was her land of milk and honey.

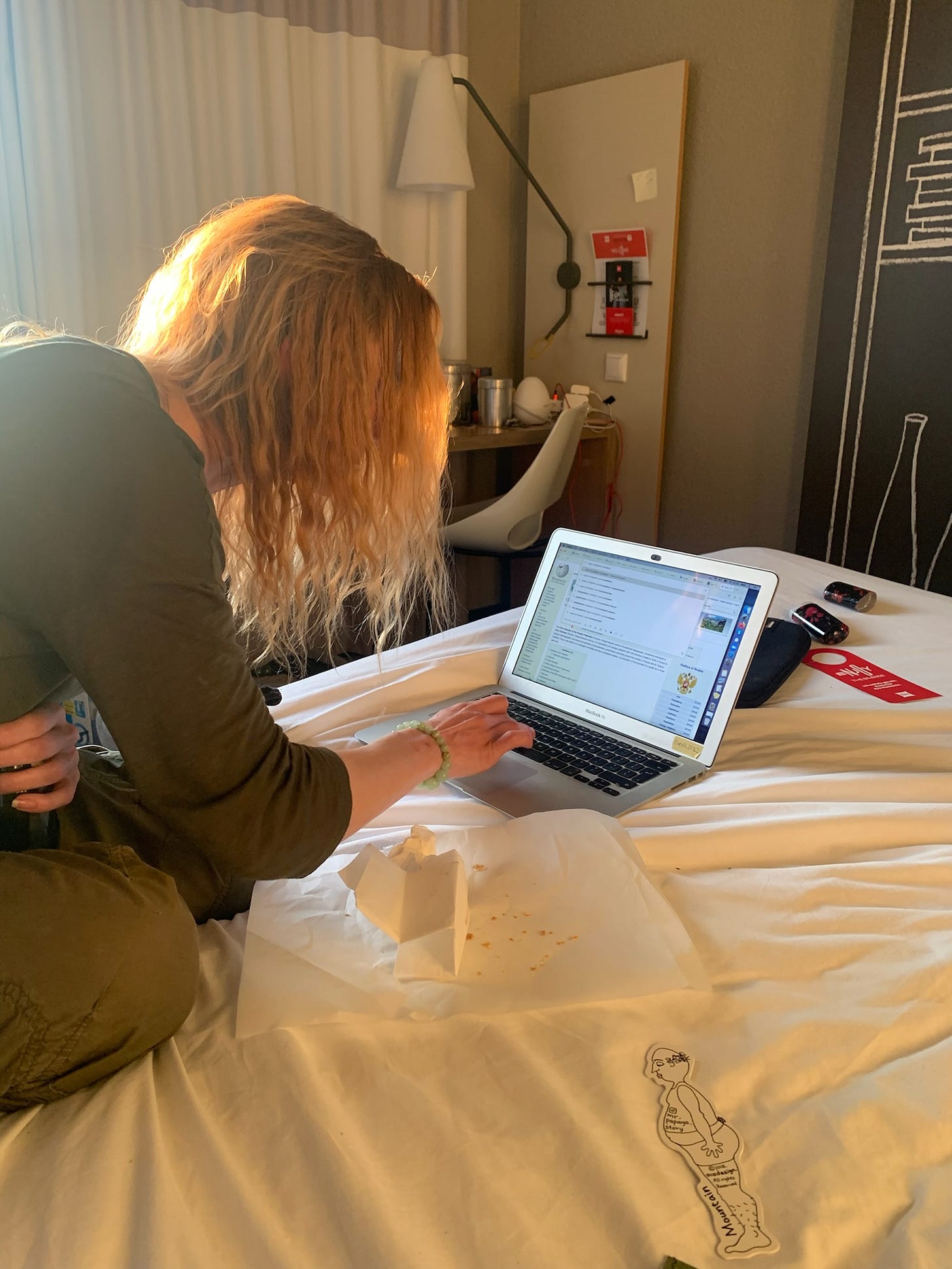

As she scrolls through the digital proof of these personal milestones and vistories, Valya grows animated for the first time. Now, I hear someone actually thank facebook’s memory function instead of bemoaning it. Valya’s dreams of being a designer based out of Odessa, of putting on shows via her contacts in London, of pursuing the possibility of a show in Italy, all of those dreams, she says sadly, evaporated in just a few weeks. To Russia, Odessa is the most important seaport for the breadbasket of Europe, and Putin’s subs have lurked on the horizon in the Black Sea for weeks now. But to Valya, Odessa is home.

Trauma-informed writing practice with a vulnerable subject demands me not to press Valya about why she demurs on certain topics or glosses over certain details. Rather, it asks me to grant a wide berth to the subjects Valya declines to talk about more. The reason her marriage declined, her career in social work, the details of the train ride to the Polish border, and the first hosts she had in near Bremmen – she’d rather not talk about those, and it’s unethical for me to guess too vividly. And so, the important part of Valya’s story is what is happening now, who she is, and what her future might look like. “Refugee” is a temporary title, and Valya is much more than that.

Next: Part V: The kindness of strangers